D.H. Lawrence suggested a book lives as long as it is unfathomed. “Once a book is fathomed,'' wrote Lawrence, “once it is known, and its meaning is fixed or established, it is dead”.

Presented with a sequence of images, the human mind instinctively works to penetrate, attach meaning and construct explanations. On first inspection, the banality in the black-and-white scenes captured in Wouter Van de Voorde’s Safe suggests this is a work that can be fathomed. On closer inspection, however, an engaging and ultimately abstract dialogue between the narrative elements of observation and the subversion of the representational emerges, opening up multiple lines of interpretation. Unexpectedly, in its simplicity, we find complexity.

Hovering between night and day, Van de Voorde seamlessly blurs the distinction between the different temporalities of the events, people and places he presents. Rather than experiencing a series of logical interconnected occurrences, the viewer must reconcile and deliberate the varying viewpoints and their significance without the sequential link of chronology. It is as though the compositions themselves are manifestations of memory that transcend the circumstances of place and time.

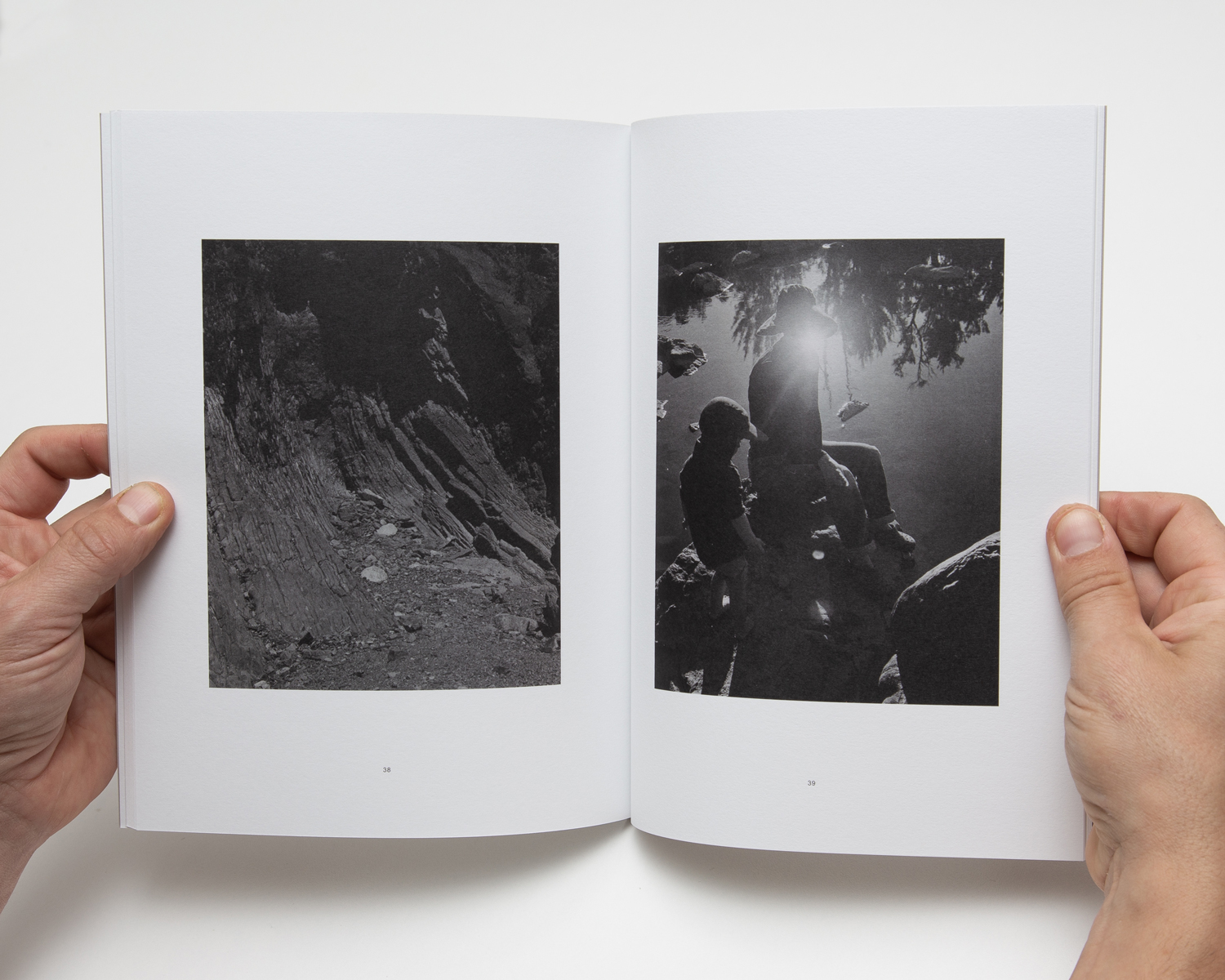

Scenes of suburbia featuring once functional but now dilapidated objects hint at a concealed, deeper meaning of objects and events. This intangible narrative characterised by ripples, disturbances and deviations from regularity is essentially what makes Van de Voorde’s work so charged. Punctuating the more narratively potent photographs are detailed botanical portraits and rock studies captured with compelling sensibility. It is in Van de Voorde’s more minimalist compositions, however, that we see a different kind of photograph emerge. In scrutinising forms and their imperfections, he subverts the representational, thus exposing and accentuating their pure form, in a dynamic discourse between form and space that echoes the work of conceptual art movements.

The underlying thread of Safe is not apparent. The viewer discerns its subjects through subtle indirections and fleeting revelations. This elusiveness is not only central to Van de Voorde’s repertoire, but is crucial to the way in which the photographs play on our imagination. In this sense, the book meets Lawrence’s criterion; we do not succeed in uncovering its meaning, but instead satisfaction is derived through the exploration of the contexts and layers of interpretive possibilities it presents.

In our desire to define ourselves we place meaning on the landscape around us, we rationalise and commodify it; we tell stories of it and we claim ownership of it in neat package deals. We image it too, in paintings, in photographs, and through memory. Consider the history of landscape photography in Australia as a series of gross public overshares – self-serving attempts at rationalising and overcoming the land, tying sites to historical identity and collective memory which are understood through standards inherently tied to the lands own colonisation. These images hang on the walls of your doctors surgery, they welcome you into the country at the airport, coerce you to invest in your next holiday, and hang in the walls of our national institutions. Time and again the images we choose to re/produce act as masks for the ecocidal practices of land clearing, habitat loss, and erasure of Indigenous land ownership; and speak to the false nationhood that is foundational to our suburbs, and our way of living. These standards of beauty and definitions of being are begging to be unwritten – because if nothing else the landscape in Australia holds secrets, it presents lies and it holds truths.

Wouter Van de Voorde traces secrets in his own relation to, and representation of, the land around him. Shot across the lands of the Dharawal, Boon Wurrung, Yuin and Ngunnawal peoples, as well as in France and Belgium (his country of birth) this body of images pictures relations and conversations over land. They suggest at the shared form of a thicket of trees, a wooden sword and a timber fence. Between a monolithic rock face and the shape of a national monument, or its reflection on water and the echo of three half submerged figures. This collection of images traces absence, and speak to the multiple histories places can hold. From fallen barriers, degraded and overgrown with weeds, to discarded objects, smashed windows, sunglasses on a trampoline. In many cases objects in the foreground obscure the read of the image, and make it difficult to work out what sits beyond.

History is involved continuously in the making and remaking of ideas about place. Van de Voorde’s subjects range from the monolithic to the suburban, and repeat in form in unexpected ways. They speak to the passage of people over time, and through the attention they prescribe to the unspoken, they challenge dominant collective understandings and representations of the country we find ourselves on.

Presented with a sequence of images, the human mind instinctively works to penetrate, attach meaning and construct explanations. On first inspection, the banality in the black-and-white scenes captured in Wouter Van de Voorde’s Safe suggests this is a work that can be fathomed. On closer inspection, however, an engaging and ultimately abstract dialogue between the narrative elements of observation and the subversion of the representational emerges, opening up multiple lines of interpretation. Unexpectedly, in its simplicity, we find complexity.

Hovering between night and day, Van de Voorde seamlessly blurs the distinction between the different temporalities of the events, people and places he presents. Rather than experiencing a series of logical interconnected occurrences, the viewer must reconcile and deliberate the varying viewpoints and their significance without the sequential link of chronology. It is as though the compositions themselves are manifestations of memory that transcend the circumstances of place and time.

Scenes of suburbia featuring once functional but now dilapidated objects hint at a concealed, deeper meaning of objects and events. This intangible narrative characterised by ripples, disturbances and deviations from regularity is essentially what makes Van de Voorde’s work so charged. Punctuating the more narratively potent photographs are detailed botanical portraits and rock studies captured with compelling sensibility. It is in Van de Voorde’s more minimalist compositions, however, that we see a different kind of photograph emerge. In scrutinising forms and their imperfections, he subverts the representational, thus exposing and accentuating their pure form, in a dynamic discourse between form and space that echoes the work of conceptual art movements.

The underlying thread of Safe is not apparent. The viewer discerns its subjects through subtle indirections and fleeting revelations. This elusiveness is not only central to Van de Voorde’s repertoire, but is crucial to the way in which the photographs play on our imagination. In this sense, the book meets Lawrence’s criterion; we do not succeed in uncovering its meaning, but instead satisfaction is derived through the exploration of the contexts and layers of interpretive possibilities it presents.

Sara Jitjindar, 2019

In our desire to define ourselves we place meaning on the landscape around us, we rationalise and commodify it; we tell stories of it and we claim ownership of it in neat package deals. We image it too, in paintings, in photographs, and through memory. Consider the history of landscape photography in Australia as a series of gross public overshares – self-serving attempts at rationalising and overcoming the land, tying sites to historical identity and collective memory which are understood through standards inherently tied to the lands own colonisation. These images hang on the walls of your doctors surgery, they welcome you into the country at the airport, coerce you to invest in your next holiday, and hang in the walls of our national institutions. Time and again the images we choose to re/produce act as masks for the ecocidal practices of land clearing, habitat loss, and erasure of Indigenous land ownership; and speak to the false nationhood that is foundational to our suburbs, and our way of living. These standards of beauty and definitions of being are begging to be unwritten – because if nothing else the landscape in Australia holds secrets, it presents lies and it holds truths.

Wouter Van de Voorde traces secrets in his own relation to, and representation of, the land around him. Shot across the lands of the Dharawal, Boon Wurrung, Yuin and Ngunnawal peoples, as well as in France and Belgium (his country of birth) this body of images pictures relations and conversations over land. They suggest at the shared form of a thicket of trees, a wooden sword and a timber fence. Between a monolithic rock face and the shape of a national monument, or its reflection on water and the echo of three half submerged figures. This collection of images traces absence, and speak to the multiple histories places can hold. From fallen barriers, degraded and overgrown with weeds, to discarded objects, smashed windows, sunglasses on a trampoline. In many cases objects in the foreground obscure the read of the image, and make it difficult to work out what sits beyond.

History is involved continuously in the making and remaking of ideas about place. Van de Voorde’s subjects range from the monolithic to the suburban, and repeat in form in unexpected ways. They speak to the passage of people over time, and through the attention they prescribe to the unspoken, they challenge dominant collective understandings and representations of the country we find ourselves on.

Rebecca McCauley, 2019